November/December 2018

By Rachel H. Pollack

Tires are tough. How tough? The president of a California-based manufacturer of tire processing equipment puts it this way: “If you have a piece of tire on the sidewalk and try to pound on it with a hammer, it will never break apart.” That’s not something you can say about many other manufactured products that enter recycling facilities.

Tires are tough. How tough? The president of a California-based manufacturer of tire processing equipment puts it this way: “If you have a piece of tire on the sidewalk and try to pound on it with a hammer, it will never break apart.” That’s not something you can say about many other manufactured products that enter recycling facilities.

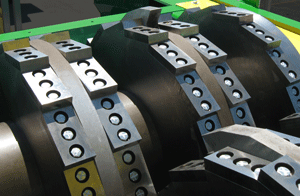

To recycle a whole tire, a processor needs a piece of equipment that’s even tougher. Manufacturers of the slow-speed, high-torque shredders recyclers use for primary tire shredding emphasize the equipment’s robustness, touting large-diameter shafts, harder steel knives, and other design improvements that allow the machines to slice through the rubber, fiber, and metal wire, turning even large and thick tires into pieces a few inches across. Slicing, not tearing, is key, they say.

If you’re a tire recycler ready to purchase a new primary tire shredder, you can shop among quite a few manufacturers who sell equipment into this market. Here’s a look at the factors you’ll likely consider when making a purchase, plus what you can do to prolong the shredder’s life and maximize return on your investment.

Purpose-built or multi-material?

Some companies manufacture slow-speed, high-torque shredders specifically for the tire market; others design them to handle a variety of materials, depending on blade design and configuration.

Liberty Tire Recycling’s (Pittsburgh) 25 primary tire shredders come from at least four different manufacturers, some of which specialize in tires and others that don’t. If you’re preparing tires for further processing and “the cut doesn’t mean a lot,” many brands of “hook-and-shear shredder” will do, says Mike Rembold, vice president of equipment and technology. For material going straight from the primary shredder to the tire-derived fuel market, he gives the nod to two brands for providing “a cleaner cut.”

The specialized manufacturers say tire rubber is unique and deserves a unique shredder design. A high-powered, hydraulically driven shredder could rip the tires apart by force, inflicting damage that “causes the shredder’s useful life to depreciate rapidly,” the California company president says. But the lines between purpose-built and multi-material shredders continue to blur. Several multi-material shredder companies promote the abilities of their largest, heaviest dual-shaft machines to handle tires. A manufacturer based in France, for example, offers two dual-shaft shredders it has designed for multiple materials, including tires, and a single-shaft machine just for tires. And some manufacturers that previously focused on the tire market are promoting shredders for additional uses. A Florida-based manufacturer now sells what it calls a “hybrid” shredder. “It was formerly used 100 percent for tires, but now you can remove the rotor and knives and install a different knife system that is more application-based,” the shredder sales manager says. “You can use them for a lot of things: wood pallets, paper, white goods, pharmaceuticals, electronics waste, steel drums,” and more. Once you develop technology in tire processing, the other materials are “a piece of cake,” adds that company’s shredder sales and marketing director.

Shaft quantity and design

Slow-speed, high-torque shredders come with one to four shafts, with two shafts the most common for primary tire processing. A two-shaft shredder is easier to maintain, says the general manager for a manufacturer based in Indiana. The international vice president for a Texas-based manufacturer agrees. “The maintenance cost goes up” on four-shaft shredders, “and people are not [happy] with that additional cost of operation.”

They both note that smaller processors might prefer a four-shaft machine. The Indiana manager defines “small” as a company that only handles “10 to 12 semi loads of tires a day,” whereas the Texas vice president puts it in terms of operating space. “It’s better for a small footprint. … If you don’t have the floor space for screens, conveyors, and a power unit” for further processing, a four-shaft shredder can process material down to a smaller chip size. To do so, operators must feed the machine more slowly, he notes.

Primary tire processing calls for a larger rotor shaft than other materials might require, these companies say. “The loads on the bearings are much greater with a smaller-diameter shaft,” the California president explains. “You’ll have a problem with bearings wearing out or the shaft breaking, which could be catastrophic to the shredder.” The bigger the diameter of the shaft, the bigger the bearings can be on the end of the shaft, he says. His shredder has a 9.5-inch shaft diameter; the Indiana company offers an 11-inch shaft. A German company with U.S. headquarters in Charlotte, N.C., offers models with shafts from roughly 19 to 29 inches in diameter with blades welded to the shaft, which it says is a unique design.

Some companies say their hexagonal shafts are superior to round shafts. Others highlight the distance between shaft centers. Kip Vincent, owner of Colt Inc. (Scott, La.), and others point out the greater that distance, the larger the tires it can process.

Electric or hydraulic?

For years, hydraulic drives were the most common for primary tire shredders. Now electric drives seem to prevail, although many manufacturers still offer both. Rembold estimates that Liberty has six times as many electric shredders as hydraulic. He doesn’t consider one superior to the other, but he notes that the largest shredders Liberty has purchased are hydraulic. “For really big tires, hydraulics are a bit more forgiving,” he says.

“With the flexibility of hydraulics, an unshreddable item can be sent back in three seconds or less,” the Texas vice president explains. “Electric drives can take 10 to 15 seconds for that to occur. They can’t react as quickly as hydraulics, so they load the shaft and the gearbox to a much higher stress level.” Why doesn’t that give hydraulics the edge? “Customers don’t want to deal with hydraulic fluids” and the mess and hazards they can create, he suggests. Plus, “electric shredders are much more durable than [they were] a decade ago.” A few years ago his company started offering a hybrid drive designed to offer the best characteristics of both, but its variable high speed and high torque were not valued by tire processors, he says.

Indeed, slow is the way to go for tire processing, with optimal speeds ranging from 9 to 40 revolutions per minute. “You’re truly producing torque, not speed,” the Texas vice president says. Generally the two shafts run at the same or slightly different speeds. On his company’s shredders, “you can change the speed by putting a different number of hooks on one shaft versus the others,” he says, with most users choosing either two or three hooks per shaft.

There’s considerable variation in the horsepower these motors generate. The California and French companies offer primary shredders with 75 hp per motor, with others ranging from 125 hp to 650 hp. Lower horsepower is “a plus because [it’s a] lower operating cost,” the Florida-based sales manager says. “If a machine truly cuts, you don’t need additional horsepower to destroy the tire. Cutting the tire is a more efficient way of processing it.” Vincent, who uses 75-hp primary shredders, says even with that little power, “it will eat 3,000 tires an hour if you can feed it that fast.”

Processing capacity

Vincent’s point is a good one, these manufacturers note. The primary shredder’s throughput depends greatly on how quickly you can feed it tires. The Texas company sells primary shredders that range in capacity from 4 or 5 tons per hour to 15 or 20 tons per hour. The larger machines can process more than that, the vice president says, “but most people can’t load or feed much more than that—the logistics are too cumbersome.” If a processor can unload each trailer of tires in 35 minutes, its largest shredder can achieve 14 or 15 tons per hour, “but not many people are pushing even that [limit].” The exception, he says, are facilities shredding tires to be used as landfill daily cover. “You can do higher rates [with a] wide cut,” making pieces “half the size of your leg. Those applications could feed 20 tons per hour or slightly more.”

The California company says 20 tons, or 2,000 car tires, per hour is its maximum throughput. “That’s not [feeding it] single file,” the president says. “That’s loading with a front-end loader or multiple trucks being unloaded at once. Some guys put in a long conveyor belt, 60 feet long, and back up trailers to that, and have multiple guys unloading trailers at the same time.” Vincent says Colt’s setup is similar to that: It uses a skid-steer loader with a grapple attachment to feed tires onto a flat conveyor belt 50 feet long, 6 feet wide, and 3 feet off the ground that runs into the shredder mouth.

Consistent feeding is a challenge, Liberty’s Rembold says. Because employees are grading the tires as they unload them, and perhaps removing 10 to 15 percent of the tires in that process, that creates gaps in the infeed stream. “Coming up with ways to feed it more consistently, we’d get our cake and eat it too,” he says. “We’re looking at ways to feed it better, maintain it, and keep metal out of it.”

Maximum tire size

Most companies give the maximum tire size a shredder can accept in terms of tire diameter or the dimensions of the cutting chamber opening, with many ranging from 4 to 6 feet in each direction. Some are 8 by 12 feet or larger.

Most car and truck tires are less than 4 feet in diameter, Vincent says, but tires for agricultural and mining equipment can be much larger. With a larger opening, “you can put bigger-than-truck tires in without pre-shearing them.” The French company says its largest machine, a single-shaft shredder, can take up to 9-foot-diameter tires.

A large chamber opening isn’t necessarily designed for one large tire, but for multiple tires at once, the California company president says. And tire diameter is not the only measurement to consider, he points out. A 60-inch-diameter farm tractor tire is “pretty wimpy,” he says, whereas a 60-inch-diameter airplane tire, designed to hold much greater air pressure, would be more taxing.

“The biggest tires most people get, and the hardest for most people to deal with, is a super-single tire,” he says, such as that used on a cement truck. He’s confident his shredders can handle those “and bigger,” but certain mining and construction-vehicle tires might be beyond its capacity. He suggests that recyclers consider their infeed—will it be an occasional truck tire or a steady diet of truck tires?—and look for a shredder that can process it.

Knife design

Primary shredding is all about the knives, and each manufacturer touts the benefits of its design, from the metal characteristics to the shape, number, and arrangement of knives on the shaft. Hooked knives are prevalent, with the hooked shape designed to grab the tire and pull it into the shredder.

Some companies offer a variety of knife designs or arrangements for different tire-shredding applications. The U.S. president of the German company says its knives vary in their hardness coatings and shape. “We typically use the hooked shape, but it depends on the client and what the client’s going to do with the material.”

Primary shredder operating costs depend largely on knife management. Thus, companies try to stand out not only in knife design but also in ease of knife replacement and how many times the knives can be sharpened and reused. “Everybody makes a shredder that will shred a tire,” the California president says. “The issue really is, how long do the blades last ... before you have to change them? If you’re shredding 60,000 tires [on one set of blades], there’s a certain cost associated with that. It’s the cost per ton. … My shredder will do 10,000 to 15,000 tons before you have to sharpen the blades.” Other manufacturers say their blades have a six-month lifespan at maximum processing capacity.

Most manufacturers say you can reuse or resharpen their knives two to seven times. Some companies note that after several uses in a primary shredder, their knives can then move to their secondary shredding equipment. The Indiana manufacturer says its blades can handle 30 to 40 rebuilds due to the material and manufacturing process they use. “The initial blade cost is much more, but the cost per ton over the life of the machine is way less,” the general manager says.

One more knife factor these companies use to distinguish themselves is how tight the tolerances are between the knives. Think of the knives as rotating scissors, the Texas vice president says. The closer they are to each other, the more pressure and energy they can put into cutting. “As knife clearances get greater, as the blade gets dull, more power is needed to do the same task.” Tight tolerances ensure “that you’re cutting the tire, not ripping the tire apart,” the California president says. These companies advertise tolerances ranging from one one-thousandth to five one-thousandths of an inch.

The state of the art

With the basics of primary shredding fairly well established, companies are making incremental improvements to their equipment to make it more robust, resistant to damage, and easier to maintain. The Germany firm says it has increased the size of the gearbox on its primary shredders for higher torque and lower speeds. The Texas company has changed the seals around its bearings to keep out tire wire, going with a “labyrinth” seal design. “Instead of a disk facing a disk, [there are] protrusions and recesses from one disk to the other,” the vice president says. “The wire [would have] to move through a maze to cause grief. It’s an effective way of preventing wire from causing bearing and seal issues.” The California company recently changed the design of the mechanism that strips the tires out of the shredder, going from a stationary to a rotating stripper design. The Indiana company has moved the drive end bearing from the inside shoulder to the outside so processors can change it without removing the blades. It also switched to larger shafts and bearings.

Liberty’s Rembold mentions most companies now have an auto-reversing feature, which clears jammed material automatically. The Indiana manufacturer has similar technology in its programmable logic controller-run shaft. “We can do a cleanout mode … to clean out between the rotors while in production,” the general manager says. “It’s programmed into the PLC, the automatic shaft cleanout, [where one shaft] goes in reverse and the other goes forward. … You can set the increment as often as you want.” The design does not require cleaning fingers or external screens, he says.

These machines require little maintenance other than blade changes, the manufacturers say—mostly lubrication and seal replacement—but making even that maintenance as easy as possible is a plus. “We put out daily, weekly, and monthly maintenance [recommendations],” the Texas vice president says. “Most you can do in 15 to 20 minutes per day.” Tasks include torquing the tensioning bolts—“you must keep them tight to keep cutters at their original clearances,” he says—greasing bearings, and inspecting the cutting chamber. (He urges processors to use proper safety procedures during maintenance, most notably lock-out/tag-out. A worker at a Houston-area tire recycler died earlier this year while trying to clear a jam in a shredder.)

A PLC manages many maintenance tasks on the Indiana company’s primary shredder, such as greasing and water misting, and the bearings have temperature sensors that sound an alarm if they overheat. “Routine maintenance basically is checking for buildup outside the splash plates,” the general manager says. These shredders were “made with the maintenance guy in mind.”

Technologies that ease access to the cutting chamber are becoming prevalent as well. On the French company’s shredders, hydraulic rams tip the feed hopper away from the shredder box for access. The Indiana company offers “lift and swap” cutter shafts: After operators remove the hopper and the side walls, the cutter shafts lift out. “You don’t have to service the blade in the shredder, you can service it off site,” the general manager says, while a replacement set of shafts keeps production moving. It takes “two hours instead of two days to change the blades. [You can be] running within three hours.”

Decision points

When selecting a primary shredder, these representatives say, take into account the nature of your operations, the equipment, and the manufacturer. In terms of operations, consider “the size tire you want to run,” the California company president says—whether passenger car, truck, or off-the-road—as well as the volume you expect to handle. “Customers want to do bigger tires [and] higher tonnages,” the Texas vice president says. The equipment is a fixed cost, he points out, so “tonnage is livelihood. The more tons you put through the system, the lower the operating costs.”

In addition to the specific features mentioned above, these manufacturers urge buyers to consider the equipment’s overall strength, whether in terms of the torque it creates, its durability and efficiency, or even its weight. “Heavy-duty tire shredders are built extremely tough” because the stress on them is substantial, the Texas vice president says. “Shredders used for [other materials] can be lighter,” but tire shredders should have “bigger bearings, larger shafts [and] sidewalls, and the gearbox and frame [should be] heavier.”

The U.S. president of the German firm agrees. Shredders with “the same shaft diameter might have different weights, which is an indication of the reliability and robustness of the machine,” he says. Its primary shredders range from 20 to 35 mt; other companies list weights from 4 to 28 mt.

Weight is “a pretty good indicator of what’s in the machine,” the Texas vice president says. “If you have two shredders with similar capacity, and one is 30-percent heavier than the other, do your due diligence, but I’d [favor] the heavier machine.” The bottom line, he says, is “you can’t make a heavier shredder with thinner steel.”

Each company tries to play up what it offers that the others do not. Smaller firms tout their ability to work directly with buyers to adapt equipment to their needs. The California president says his company only builds five or six shredders a year, but as the owner and the designer, he can easily make changes to the design based on customer feedback. “A large company making 20 to 30 a year has an inventory stream, they can’t just make changes [for one customer] and throw away 30 shredder parts to make the change,” he says.

The French firm and the Indiana firm point out that their companies have related processing businesses. Being both a manufacturer and a user of the equipment “helps us best understand the needs of our customers,” the French firm says.

Other companies point out their stability and longevity in the business, number of installations for primary tire shredding, and availability of service and support. “Look at your vendor as a business partner,” the Texas vice president says. For maintenance or knife changes, “you need a vendor that can be there. You’ll deal with him week after week, month after month.” He urges buyers to get recommendations from existing tire processors, too.

Return on investment

Primary shredders from these companies largely range in price from $180,000 to $500,000, with one company offering its largest models for more than $1 million. That price does not include conveyors or downstream processing, they note.

The California president cautions against buying less shredder than you really need. “Guys will say, ‘I like your shredder, but can you make the shredder cheaper and smaller? I don’t [process] that many truck tires.’” That’s like asking an engineer to build a cheaper bridge because heavy trucks will only drive over it once in a while, he says. You must design the equipment for the maximum load it will receive.

A primary shredder’s useful life will vary based on the volume it handles as well as the care and maintenance the operators provide. “Doing the proper maintenance will extend the life of any machine,” the Florida sales manager says. Most companies suggest their shredders will last 7 to 10 years with average care, but twice that or more—up to 25 years—if they’re well cared for. “It’s ‘pay me now or pay me later,’” the Texas vice president says: “If you’re not spending maintenance dollars every day, week, and month, you’ll have a catastrophic failure, and then you’ll be spending more than you would with routine maintenance.”

These sellers and users agree on the two actions that will prolong a shredder’s life. The first is to sharpen and change the knives at the proper interval. “The worst thing [you can do] is to let the blades get dull,” Rembold says. The shredder performance “just gets worse and worse.” You might save money on the blades, but you’ll wear out the shredder more quickly, he says. “Good plants have a program to religiously go in at X amount [of processing volume] and do blade maintenance. Others have great blade costs, but their throughput goes to hell.”

Worn blades, in addition to losing their sharpness for cutting, are farther apart, meaning the equipment is more likely tearing, not cutting, the tire. That requires more torque, which taxes the equipment more, and could even break a shaft. Blades that are run too long also can get so worn they can’t be refurbished, so the processor only gets one or two uses out of them instead of a half-dozen or more, the Texas vice president says. Processors “thought they were reducing maintenance costs, but now they’re replacing knives instead of maintaining them,” he says.

The second action that will extend a primary tire shredder’s life is to feed it tires and nothing else. Most of these companies say the equipment can handle an occasional metal tire rim, but a steady diet of metal rims will cause excess wear on the knives or break them. “We don’t want to be processing rims,” the Florida sales manager says. “It’s a tire shredder, not a rim shredder.” The damage is cumulative, the California president says. “You might get away with it a bunch of times, but eventually something’s going to happen.”

Both Vincent and the Indiana general manager identify railroad spikes embedded in tires as items that can do serious damage to a primary shredder. They can break a blade, break the shaft, or fracture a gear on one of the gearboxes. Any kind of hardened metal—a sledgehammer or a blade from another shredder, for example—“really causes havoc,” the general manager says. Other manufacturers caution against excessive amounts of stone, concrete, sand, and dirt, all of which are abrasives that will wear the blades. Careful inspection of the infeed material can prevent such problems, Vincent says.

The U.S. president of the German company, which makes multi-material shredders, points out one error some buyers make: They assume a blade style and configuration designed for one material can handle other materials as well. “Scrapyards or tire [processors], if they have a machine that shreds or cuts, they will put in all sorts of material—motors, castings, whatever they have,” he says. That’s likely to prematurely wear or damage the machine.

Looking ahead

The California president says further advancements in primary tire shredding technology will depend on where the markets for recycled tire rubber are headed. The Indiana manufacturer also worries about end markets. “We are very adamant about bringing [potential customers] in, sitting down with them, and actually talking to them” about their processing goal and business plan, the general manager says. They’ll tell a potential customer if they think a facility is likely to just increase competition and drive down prices. “We would rather … lose a sale than have [the buyer] go out of business and drive three other guys out of business. We’ve never sold a piece of equipment that wasn’t used effectively.”

Rachel H. Pollack is editorial director of Scrap.

(SIDEBAR)

Two perspectives on portable tire shredding

Few U.S. customers are buying portable shredders, manufacturers say, but they see some interest in the international market. “Most [U.S.] tires now are current scrap generated day in and day out, so the need for mobility is less and less,” says the international vice president of a Texas-based shredder manufacturer. He sees more demand for portable equipment in Mexico and the Persian Gulf region.

Liberty Tire Recycling has a couple of portable shredders, but it rarely uses them, says Mike Rembold, vice president of equipment and technology. “It’s difficult to get permitting when you go to a cleanup when you’re using something like that,” he says. Still, if a facility has a major failure and it doesn’t have a backup shredder, “it would be nice to roll in a [portable] shredder” to continue operating.

A California manufacturer of primary tire shredders doesn’t offer a portable option, saying the liability is too high and the design changes it would require would be detrimental to the shredder’s performance. “When you take a piece of equipment and condense it down so it becomes portable, you compromise in a lot of areas,” the company’s president says. Buyers can mount his primary shredder on a step-deck trailer, but he won’t do it for them.

Other manufacturers say they continue to serve the portable shredder market. A Florida company’s mobile tire shredding system can process tires into chips that are roughly 2 inches across with minimal exposed wire, it says. It recently sold two such machines to the South African government to turn tire stockpiles into tire-derived fuel.

And a French company recently launched a compact, self-contained shredder-in-a-box. Its portability is more for ease of installation than frequent movement, it says. The shredder is mounted in a 20-foot container with all mechanical and electrical systems built in, plus machine guards and an output conveyor, offering “plug and run” performance for small and medium-sized tire processors, requiring almost no installation time or cost, it says.

Robust machines with high torque and tight knife tolerances are up to the challenge of turning whole tires into rough shred. properly timed knife changes and good infeed inspection can maximize your return on this investment.